Beauty n. state of being pleasing to the senses • Liturgy n. work of the people

Imagining God

by Rev. Jim Evans

So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.

Genesis 1:27

A young boy was spending the day with his grandmother. She was a devout person, but also stern. She set a high bar for her grandson’s behavior and expected him to live up to it. At some point during the day the grandmother came upon the boy while he was playing with a few action figures he had brought with him. In the course of his play, the grandmother heard her grandson talking out loud as he pretended that his action figures were real people and were talking to each other.

“Who are you talking to,” the grandmother asked forcefully.

“I was just pretending that my action figures could talk. It’s just a game I play.”

“Well, it is not a game I approve of,” said the grandmother. “In this house we do not have conversations with imaginary people. We must always and only deal with what is real, not pretend.”

At dinner that evening the grandmother called the boy to the table.

“Now, before we eat, we give thanks to God.”

With that the grandmother bowed her head and spoke a brief blessing over the food she had prepared. She finished by saying, “Amen.”

The little boy looked at her and said, “Grandma, who were you talking to?”

This little story introduces the role of imagination in our relationship with God. God is not visible to us. When we pray it would appear to someone who didn’t understand about God and prayer, that we were talking to an imaginary person. For believers, God is not imaginary—God is real. But God is different from us. God is not directly visible to us. Even though the book of Genesis states that we are created in the image of God, it does not explain exactly what that means. Clearly, we are not like God in physical appearance. So, what does being created in God’s image mean? And since God is not visible to us, how do we conceptualize God for purposes of prayer and worship?

There is always the danger of taking a thing of beauty intended as an aid to worship and turning it into an object of devotion. But in spite of this danger, human beings are nearly forced by the limits of our humanity and the deep transcendence of God, to find ways to visualize God in some form or other.

The question is complicated by the second commandment concerning the practice of making images of God out of stone or wood. Is there a difference between something visual that facilitates worship, and something visual that we worship in the place of God? The answer seems obvious but the line is easily blurred.

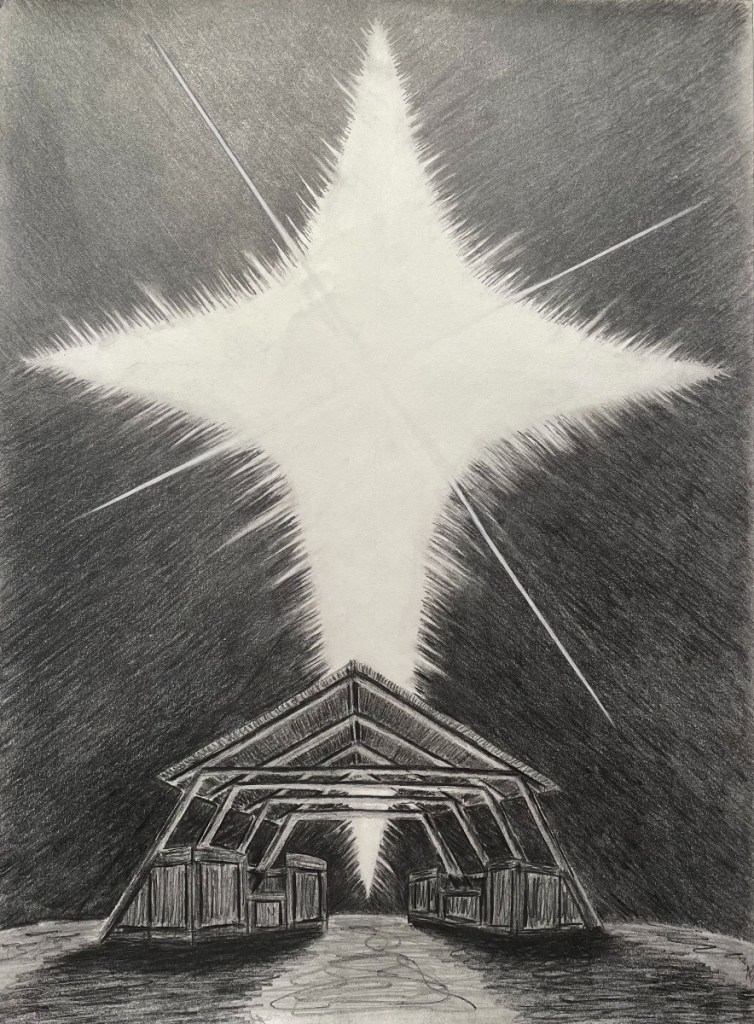

For centuries Christians have called upon the visual arts as means of promoting worship, and in some instances informing worship while trying to avoid worshiping the image rather than the God it points to. And this is not always prompted by an act of intentional art. Blazing sunsets, and powerful displays of weather often result in awe and a deep awareness of God’s presence.

The situation seems to be this. There is always the danger of taking a thing of beauty intended as an aid to worship and turning it into an object of devotion. But in spite of this danger, human beings are nearly forced by the limits of our humanity and the deep transcendence of God, to find ways to visualize God in some form or other.

The Bible itself sets the tone here. The image of God walking through the garden of Eden is powerful representation of God’s intimate connection to creation. The instructions to Moses at the burning bush were to remove his shoes because the ground around the bush was made holy by God’s presence. The bush here becomes a vivid example of God’s “otherness.” There are many more we could mention. The point being that some sort of visual or audible representation seems necessary in the development of proper worship.

In practical terms, almost anything we do can become a worship aid. Music is one example. When we lift our voices in praise singing “a mighty fortress is our God,” we have visualized God in song. Or the words used in devotional texts that portray God as light, and other powerful images, become worship aids that keep us from floundering on the reality of the unseen God.

This is especially troubling for Christians in the Anabaptist tradition as we are here at Crosscreek. In powerful opposition to the Roman Catholic church in the early sixteenth century, Anabaptists stripped their worship places of any objects of art or visual beauty. They were deliberately drab. This act of protest may have served a purpose in its time, but this is not such a time.

Industrial and technological advances compete with the arts for place in our world. It is sad to note that in many public schools there is no art curriculum at all. This absence of beauty leaves us bereft of avenues to experience God’s presence. This is not a call to recreate the art of the Renaissance, but only to open ourselves to the prospect that our own contributions of beauty are needed and welcomed.

It may in fact be part of a calling that has sadly been overlooked in our Christian experience. Religious art, music, spoken word, dance—all these and more are gifts waiting for faithful respondents to hear the call of God.

What imaginative act of beauty is God calling out in you?